Towards the end of 2017, I moved my blogging platform from WordPress to Jekyll. It was a time consuming, but an educational experience which I’m happy to have made.

When starting out I made sure to properly understand the issues I was having with WordPress and revisit my vision for the blog. This understanding was used as the basis to justify the effort and provide a measure of success and validation.

Leaving WordPress

TL:DR - Security

The move away from WordPress started when I noticed that my privacy badger browser extension reported 2 cookies blocked. Previously, it had only reported Google Analytics, but something had changed.

After investigating the change, I learnt that JavaScript used by my theme was adding tracking crap to my site. I was a bit pissed at this. After trying a number of other themes, I noticed that this behaviour isn’t uncommon. Now, I get ‘free’ is a bit of a misnomer but this was enraging especially from a security POV. I didn’t have a reliable way to validate my supply chain and therefore a chain of trust couldn’t be established. If plugins or themes were compromised, how can I know?

The simplicity of a WordPress install is a catch 22. As the process is hidden behind a one-click installer, the consumer never really learns how it works. This makes troubleshooting the above paranoia very hard and often risky. I was unable to be confident in the risk of making recommended changes to potentially resolve my issues.

WordPress doesn’t have the best reputation for security, even if components are kept up to date. The thought of my hard work being used to spread malware is rather sickening. Plugins where needed to add security, but they required a lot of permissions and like themes, I couldn’t establish a chain of trust to my personal satisfaction.

Side note: I largely blame Patrick Gray and Co at Risky Biz for this paranoia. They have done a great job over the years of highlighting the need to establish trust of a supply chain.

Why Jekyll and Static HTML

Moving to static HTML and Jekyll is the result of conversations with Grant Orchard. At the time I was looking, he had just moved to the platform. After a lot of reading, it seemed to suit my needs and I came to the realization there wasn’t a need a dynamic site provided by WordPress. The number of services and plugins required was drastically reduced, lowering my risk profile.

Being static HTML, my blog is fully portable and backed up in at least 4 separate locations, 3 of those being cloud storage and the rest local computer files.

I write most of my posts on the train as part of my daily commute and internet is spotty at best throughout the journey. Being able to write and test site changes without the connectivity is a big plus.

Content is created as plain HTML files, allowing full visibility of behaviour at the code level. An additional benefit is the ability to very quickly parse for external site references and changes in script files.

Jekyll is written in Ruby, as such platform and plugin versions are maintained through a Gemfile. While this provides tight version control, it enables vulnerability testing against versions (on the TODO list). Source code for Ruby gems is open and available to be tested and scanned, which helps with supply chain validation.

The site itself is hosted from an S3 bucket with reduced redundancy and Cloud Front provides the CDN service. This has reduced hosting cost from Approx. $12AUD per month to $3AUD, including domain registrar and DNS fees.

With security being a major focus, having platforms maintained by people much better at the task than myself is a bonus. Better resourcing, experience and pretty much better everything. This doesn’t mean security is not my problem, but it helps to remove a majority of the overhead to someone else.

The Jekyll Experience

If you want to try out Jekyll it’s helpful to have an understanding of:

- Ruby Installation

- Gem management

- Intermediate features of a text editor such as VS Code

- Understanding of Markdown

Installing Jekyll is well documented and straightforward, there’s not really anything special to note.

Migrating from WordPress was a smooth transition as there are tools which will do that for you. To perform the migration, I did need shell access to my hosted server. After the migration, you’ll likely have to deal with broken internal links and trim some irrelevant metadata from the resulting files. Internal links such as images and cross post references are easy enough to deal with as it can be done with a mass find and replace. A bit of additional effort is required if you want to move those from standard HTML tags to Markdown and code highlighting may be an issue.

Using the base theme, it’s possible to get up and running within a couple of hours. Themes, plugins and customization are where the real-time commitment comes in.

Sinking Time With Customization

If you’re not happy with the default theme or want to make your site more ‘you’, there’s some additional knowledge you’ll either need up front or learn on the way.

- CSS, HTML, SASS / SCSS

- Liquid Tags

- Jekyll plugins

- Browser developer tools

I found a theme that was ‘close enough’ and bastardized it to get what I felt best represented how I imagined the site to look.

The complexity of themes can have a drastic impact on the site build times. One took 12 minutes to build on my MBP or 5 on my desktop, this was due to a large amount of CSS / SASS being present but not used.

Understanding these languages helps reduce build times as you can remove what is not needed. My current theme takes 7.76 seconds to build, and I’m sure I can get that lower with effort. Keep in mind, if the more you customize a theme the more self-reliant you’ll need to be on maintaining your theme.

During the process, I learnt about Google Page Speed Insights, which provides data on your web page optimization. This caused major delays and headaches, but it was worth it. Specifically, removal of blocking above-the-fold content.

Many CSS themes do not tick this box. The modification requires converting from CSS to SCSS / SASS and modification to templates. The process is well documented but presents a learning curve for those (such as myself) not experienced with these languages.

During my search for themes, I learnt that many look awful on mobile phones. A common issue was the right page margin not being defined correctly, causing scrolling to the right beyond the visual boundary. This added another consideration for theme selection removing a number pretty quickly.

Getting Fancy With Pipelines

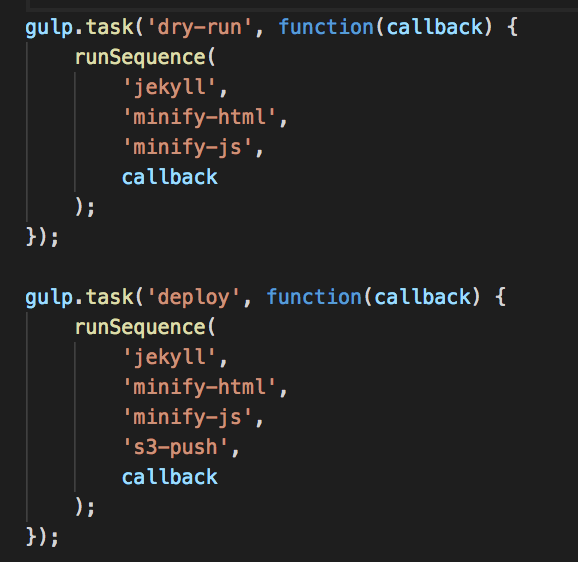

Stemming from my goal to get a high rating from Page Speed Insights, I implemented Gulp to build a deployment pipeline. The pipeline is used to perform HTML and CSS minification tasks and push the generated content to S3.

This works with local hosting to help validate that the minification process doesn’t break the site layout.

Features Lost

The move took away a couple of nice to have features from WordPress, and since moving I don’t think I’ve missed them. With WordPress, I used an SEO plugin to assist with language usage and general SEO stuff. The added language assistance it provided would have been nice to keep, but there are other tools out there.

Being able to auto post to Twitter was a nice plugin to have, but not essential. I’m planning on moving this to my Gulp pipeline using Twitters API when I get the time, but it’s low on the priority list.

Writing in Markdown was a little bit of a curve, but quick to get used to. The main pain point is using tables, I find them ugly and somewhat hard to validate in a text editor even with an MD visual plugin. There is a need to improve my process for using code blocks. With the likely approach being through text editor features.

Current Writing and Publishing Process

Posts are written in MD, using VS Code for a bulk of the work and Grammarly for language checking. After that, the built-in Jekyll built-in HTTP service is used to locally host the blog for layout and link validation, including using a Gulp task to perform optimizations.

New posts are stored in a _drafts folder, which is ignored by git not part of the final site build. After a post is completed, it’s moved to the _posts

The new post is moved from the _drafts to the _posts folder, which is then recognized as a version control change. The new post is committed and pushed to remote. The _drafts folder is in .gitignore, so these posts cannot be added to git.

With the content written and validated, a gulp deploy task is run which performs the build, optimization and pushes updates to S3. Soon this will include the git push as well.

The TODO List

Add git hooks to ensure credentials are not pushed to git

Add git push to gulp

Improve method for adding MD formatting such as links to posts. Possible text editor macros

Add vulnerability checking to Gemfile

Summary

The process of moving to Jekyll took effort, it had roadblocks and knowledge barriers. Lessons learned later on forced revisiting original concepts.

The result is a highly portable, resilient, fast and cheap site. Which should be much more secure through supply chain validation and transparency.

I’m an engineer which means the improvement and tweaking process will never stop. But at this point in time, I’m very chuffed with the result and I hope you are as well :)